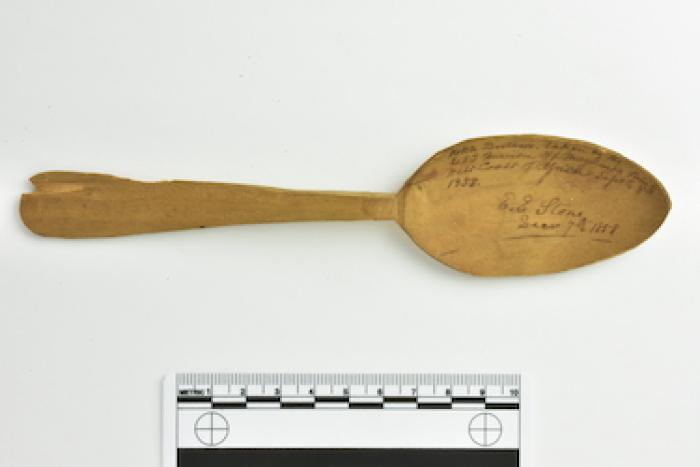

Spoon from the Brothers, 1858

The U.S. outlawed the transatlantic slave trade in 1808. Nevertheless, some Americans persisted in plying the trade illegally. From 1819 to 1861, the U.S. Navy maintained a squadron that patrolled the West African coast to arrest American slavers. This was often an unrewarding task, as sympathies within the government sometimes lay with the slavers. Depending on who was Secretary of the Navy, the squadron was often composed of only a handful ships with few guns and arrests could be overruled once they reached American courts. Despite these handicaps, the squadron’s captains pursued their mandate as best they could.

On September 8, 1858, Commander Thomas Brent, master of the USS Marion, sent notice to the Navy Department in Washington: “I have the honor to inform you that on this day I fell in with the American ketch, or yacht, Brothers, James Gage master, from Havana, bound to the River Yarve, or Congo, and that I found in her, in my opinion, ample evidence to justify her seizure as a vessel engaged in the slave trade. I have accordingly directed Lieut. E.E. Stone with midshipman N. Green and a prize crew, to proceed to Charleston, S.C., as the port to which she belongs, and to deliver her, with her crew and cargo, into the custody of the Marshal of the United States for that district.”[1]

The Brothers had left Havana on July 2, 1858, supposedly bound for the island of Sao Tome off the African coast. When intercepted near the Congo River by the Marion, it was found to be carrying extra planking (often used to construct a slave deck), wooden spoons, two extra iron boilers and bricks for a hearth, 40 extra water casks, a large lot of beans, bread, and sardines, and $8500 in Mexican gold—all things indicative of a planned slaving voyage. But the idea of seizing a ship and arresting a crew simply for suspicion of intended engagement in the slave trade did not sit well with many at the time. As a writer for the Charleston Mercury noted, “Such an atrocious novelty in law may win the pleasure or approbation of Boston fanatics, but no jury in South Carolina, we are satisfied, will ever enforce it.”[2] Indeed, a Charleston grand jury found “no true bill” for slave-trading charges against the crew, and the seized ketch and its cargo were ordered by the admiralty court to be returned to the owners.

During the Middle Passage, Africans were fed soup-like meals of beans, rice, or mashed yams, sometimes flavored with pork. Wooden spoons, along with wooden bowls, would have been provided to them at mealtimes. Slave mutinies were common during the voyage and the crew took pains to ensure that their prisoners did not have anything available to them that could be used as a weapon—although there are accounts of careless sailors being beaten to death with wooden bowls.

This hand-carved spoon is seven and a half inches long (19cm). In the bowl of the spoon is written “Ketch Brothers. Taken by the USS Marion, Mayumba Point, West Coast of Africa. September 8th, 1858. E.E. Stone, December 7th, 1858.” Lieutenant Stone apparently took some of the Brothers’ spoons as souvenirs of a victory against the slave trade, however small and ineffectual, signed them, and gave them to friends.

[1] The Ketch Brothers, Charleston Mercury, November 11, 1858

[2] Seizure of a Slaver, Charleston Mercury, November 16, 1858

On September 8, 1858, Commander Thomas Brent, master of the USS Marion, sent notice to the Navy Department in Washington: “I have the honor to inform you that on this day I fell in with the American ketch, or yacht, Brothers, James Gage master, from Havana, bound to the River Yarve, or Congo, and that I found in her, in my opinion, ample evidence to justify her seizure as a vessel engaged in the slave trade. I have accordingly directed Lieut. E.E. Stone with midshipman N. Green and a prize crew, to proceed to Charleston, S.C., as the port to which she belongs, and to deliver her, with her crew and cargo, into the custody of the Marshal of the United States for that district.”[1]

The Brothers had left Havana on July 2, 1858, supposedly bound for the island of Sao Tome off the African coast. When intercepted near the Congo River by the Marion, it was found to be carrying extra planking (often used to construct a slave deck), wooden spoons, two extra iron boilers and bricks for a hearth, 40 extra water casks, a large lot of beans, bread, and sardines, and $8500 in Mexican gold—all things indicative of a planned slaving voyage. But the idea of seizing a ship and arresting a crew simply for suspicion of intended engagement in the slave trade did not sit well with many at the time. As a writer for the Charleston Mercury noted, “Such an atrocious novelty in law may win the pleasure or approbation of Boston fanatics, but no jury in South Carolina, we are satisfied, will ever enforce it.”[2] Indeed, a Charleston grand jury found “no true bill” for slave-trading charges against the crew, and the seized ketch and its cargo were ordered by the admiralty court to be returned to the owners.

During the Middle Passage, Africans were fed soup-like meals of beans, rice, or mashed yams, sometimes flavored with pork. Wooden spoons, along with wooden bowls, would have been provided to them at mealtimes. Slave mutinies were common during the voyage and the crew took pains to ensure that their prisoners did not have anything available to them that could be used as a weapon—although there are accounts of careless sailors being beaten to death with wooden bowls.

This hand-carved spoon is seven and a half inches long (19cm). In the bowl of the spoon is written “Ketch Brothers. Taken by the USS Marion, Mayumba Point, West Coast of Africa. September 8th, 1858. E.E. Stone, December 7th, 1858.” Lieutenant Stone apparently took some of the Brothers’ spoons as souvenirs of a victory against the slave trade, however small and ineffectual, signed them, and gave them to friends.

[1] The Ketch Brothers, Charleston Mercury, November 11, 1858

[2] Seizure of a Slaver, Charleston Mercury, November 16, 1858